The Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics are finally underway after months of controversy-fuelled build-up; these games are probably the most politically turbulent since the Cold War summer Olympics boycotts of 1980 and ’84. Destined to be remembered as the Rainbow Games thanks to a backlash from the civilized world against the Russian establishment’s appalling anti-gay stance, Sochi 2014 has attracted unprecedented media attention. Not much of it has had anything to do with sport, and even less attention has been given to the venue itself.

Sochi won the competition to host the games in 2007. That same year, Dutch duo Rob Hornstra and Arnold van Bruggen set out on a mission of “slow journalism”, making frequent trips to the resort, getting to know the people and their way of life, and documenting the changes that come with winning the Olympic bid. The most you’ll see about Sochi on mainstream TV is a quick once-over package, some scenery shots and a few quirky facts and figures, but The Sochi Project – and accompanying publication, An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus (Aperture, 2013) – by Hornstra (photography) and van Bruggen (texts) is something altogether different. They have been there from the beginning, way before the camera crews flew in a couple of weeks ago, and as a result have pieced together what may be the definitive companion piece to the main event. It’s certainly an eye-opener.

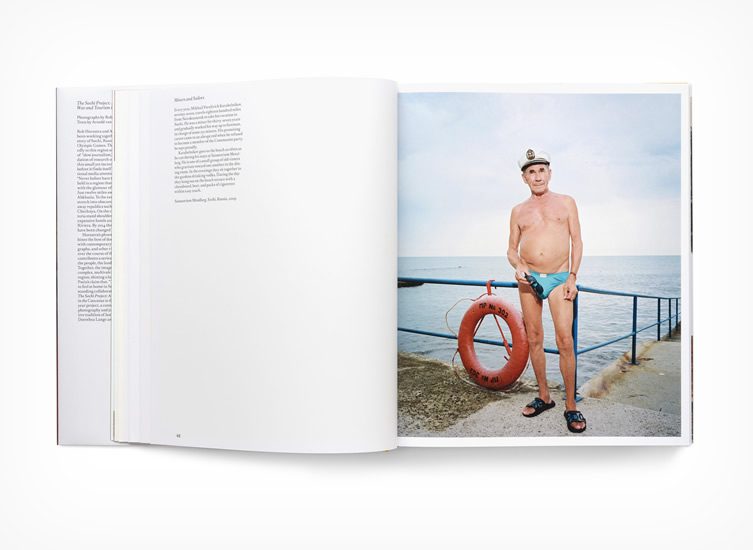

© Rob Hornstra / Flatland Gallery

Adler, Sochi region, 2011

The railway line from Sochi to Sukhum in Abkhazia hugs the coast. Behind it rise the hotel-style sanatoriums of Adler. Ordinary hotel rooms are marginally cheaper, which is immediately apparent on Adler’s seafront. The beach is full of overweight bodies sweating beer and spirits, bare torsos, noisy eaters surrounded by drunken bluster and tacky music. The locals have little choice but to put up with the visitors.

Well-heeled Russians take refuge in Sochi’s fancier hotels or opt for Italy, Turkey or Thailand. The Games may bring a level of quality that will discourage cheap tourism, but more likely the city will just become more expensive, chaotic and crowded.

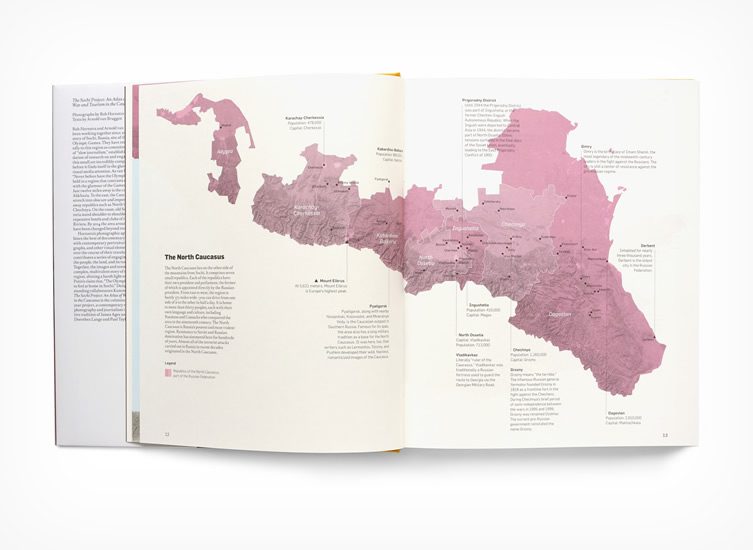

To begin with, without the Winter Olympics, few people outside Russia would have heard of Sochi. The Sochi Project dubs the resort on the Black Sea coast “the Florida of Russia, but cheaper” and for cheaper, you might substitute a few less complimentary adjectives. As van Bruggen puts it, “Never before have the Olympic Games been held in a region that contrasts more strongly with the glamour of the Games than Sochi”. It’s fair to say it was a very unusual choice of venue. The climate is subtropical, for a start. Crammed full of sweaty sunbathers in the height of summer, it’s a ghost town in winter, and along with people, something else you won’t find a lot of is snow – not until you head into the mountains anyway. Just getting there is an ordeal; by land it’s a 37-hour journey south from Moscow through the back of beyond, and on arrival, it might be tempting to brave the return leg sooner rather than later. Sochi is 20 kilometres from the war-zone of Abkhazia, a breakaway Georgian territory. The blinged-up properties of the Russian Riviera elite stand in uneasy contrast to neighbouring Soviet sanatoria.

This is also the most expensive winter games by an Olympic mile – estimates put the total cost in excess of US$50 billion. The troubled regions on the other side of the Caucasus mountains may not see much meaningful investment, but Sochi is getting a whole new lease of life. Hornstra and van Bruggen have chronicled the economic developments brought by the Winter Olympics, and explore the cost of this investment, not least from the point of view of civil liberties amid brutal crackdowns from the state in the run-up to the games, fearful of political unrest being televised around the world.

The Sochi Project website, www.thesochiproject.org, contains a number of photojournalism articles, as well as a shop stocking special edition books, posters and photographs focusing on various aspects of the long-running investigation. You can also donate to the project, which is a crowd-funded venture.

***

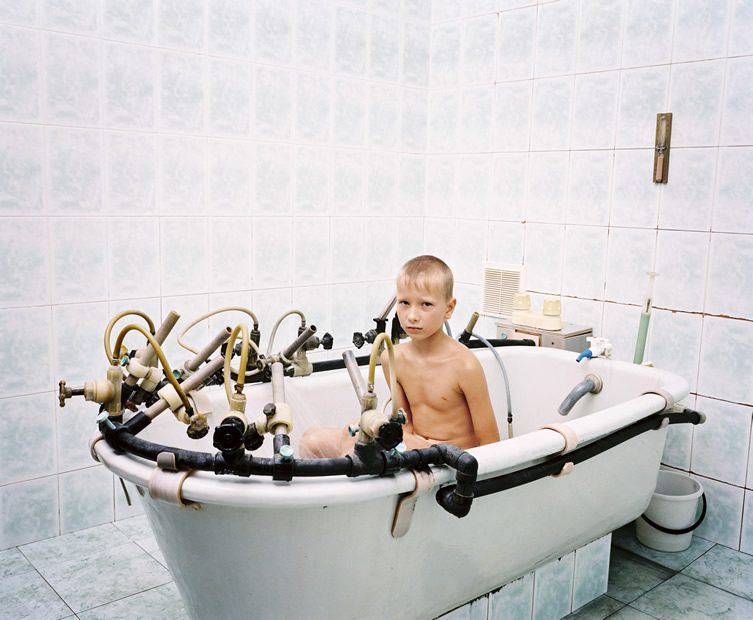

© Rob Hornstra / Flatland Gallery

Sanatorium, Matsesta, Sochi region, 2009

Matsesta, a village just inland from Sochi, is renowned for its sulphur baths, its name means ‘fire water’. There is a treatment for every ailment and busloads of visitors arrive each day to improve their health. Outside the sanatorium an entire industry has developed of old ladies selling honey, herbal teas and birch-bark scenes.

Young Dima had burned his legs at his parents’ barbecue party and his doctor prescribed a visit to Matsesta. The treatment involved sitting with his burned legs under running sulphurous water for six minutes, three times a day. His nurse said that any longer and the remedial effects of the water would be worse than the complaint.

© Rob Hornstra / Flatland Gallery

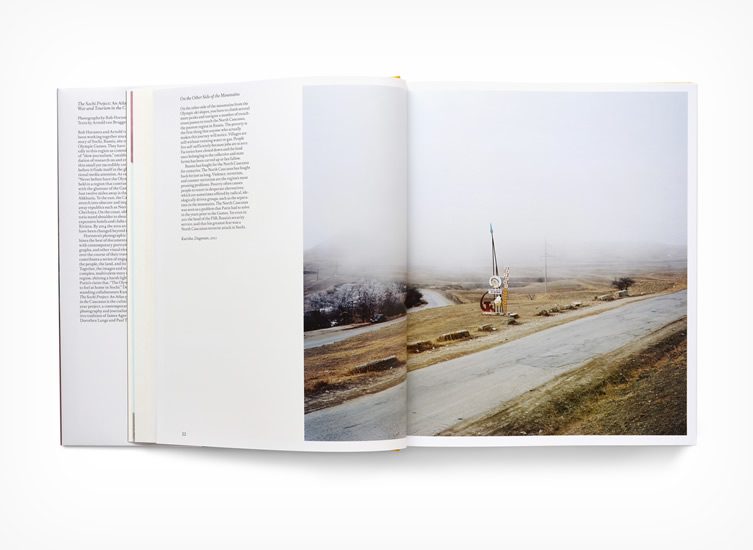

Rosa Khutor, Sochi Region, Russia, 2013

Rosa Khutor is an alpine ski resort in the Krasnaya Polyana valley, 25 miles from Sochi. Its main investor is Vladimir Potanin, an oligarch who has put $2.2bn into the development. Modern, eclectic, and flashy, it is a small embassy of planet Moscow in the Caucasus, President Putin’s dream of a new Russia has become reality.

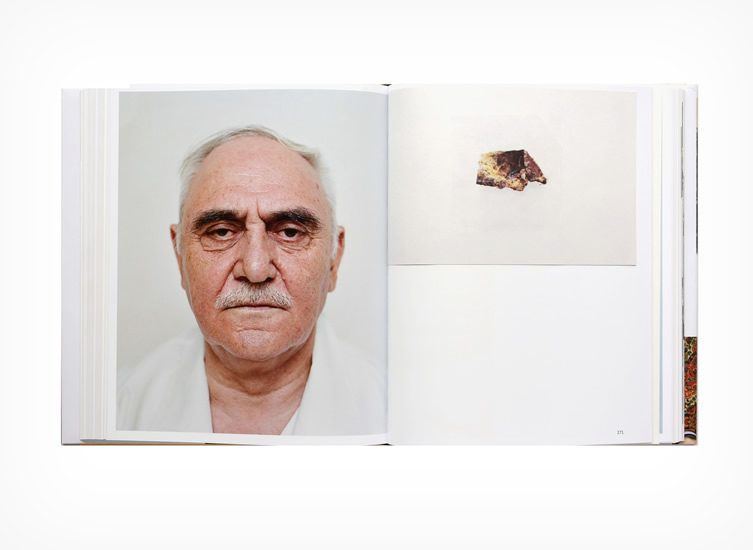

© Rob Hornstra / Flatland Gallery

Gimry, Dagestan, 2012

The road to Gimry‚ a centuries old center of the anti-Russian resistance‚ winds through stunning scenery. We stop to photograph the village from the other side of the valley. Then two cars pull up and men in leather jackets get out. We are under arrest. ‘Can’t we go to Gimry?’ I ask the leather jackets. ‘Of course not,’ one of them replies curtly.

All images: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus

(Aperture, 2013). ISBN 978-1-59711-244-4

© Rob Hornstra / Flatland Gallery

Captions courtesy, Rob Hornstra and Arnold van Bruggen